Solving the Unsolved: True Crime 2014

Die-hard mystery fans won’t be able to resist these real-life cold cases

By Lenny Picker

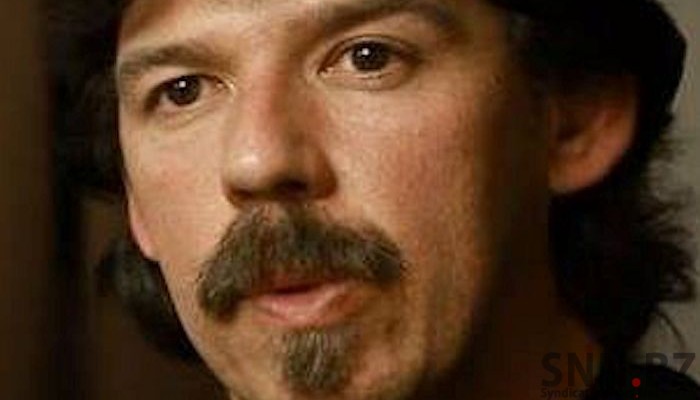

Todd Matthews started as an amateur sleuth, using the internet to connect missing persons cases with unidentified bodies in morgues. He is now regional director for NAMUS, a Justice Department project to carry on the same work. Matthews works out of his home in Livingston, TN.

The role of the Internet in identifying criminals, and the growing phenomenon of “Web sleuths,” is at the heart of Deborah Halber’s The Skeleton Crew: How Amateur Sleuths Are Solving America’s Coldest Cases (Simon & Schuster, July).

The book follows the story of Todd Matthews, a Tennessee factory worker, who, at age 17, became obsessed with a cold case involving a young woman who died before he was born. He had heard about “Tent Girl” from his then-girlfriend’s father, who’d stumbled on the body stuffed in a carnival tent by the side of a Kentucky road.

Todd spent 10 years searching for her identity, but it wasn’t until the advent of Internet bulletin boards in the late 1990s that he spotted a notice posted by the sister of a woman who’d been missing since 1968. DNA and new forensic techniques identified Tent Girl as Barbara Ann Hackmann, whose husband, a carnival worker, had left their three children with relatives, claiming Barbara Ann had run off with another man. He became the prime suspect.

Matthews’s success as the first Web sleuth led to new digital databases devoted to unidentified victims. One of these, the Doe Network, attracts Web surfers who want to play private investigators. Halber’s book features a truly eccentric cast of armchair detectives: “a police dispatcher from the projects in Quincy, Mass., whose nephew had been brutally murdered; a one-time pig farm manager whose remarkable Internet research skills have made her indispensable to law enforcement; a craftswoman in South Carolina whose foster sister had mysteriously gone missing and turned up more than 25 years later as a skeleton with a bullet through her skull; and a woman in Mississippi, who managed to solve a case in which the only clue was a man’s head encased in a bucket of cement.”

Appropriately enough, Halber learned of her heroes via the Web. As she explains, “I found on Internet databases a small city’s worth of unidentified human remains…. By some estimates, there were tens of thousands of bodies, languishing in back rooms of morgues and buried in potters fields. It was one of saddest examples of national neglect I had ever come across. Then I found the DoeNetwork, and Todd Matthews, and I realized there were people out there who were bypassing law enforcement, taking matters into their own hands, trying to match the missing with the unidentified.” She was surprised that people would take on such a morbid, seemingly futile hobby, and that they were succeeding in solving cases.

That success can be directly attributed to the Internet, which made it possible for individuals to create databases of existing material on Jane and John Does from newspaper archives and other sources and gather it in one place. Halber observes that “unlike law enforcement, which tends to work in small fiefdoms dictated by local geography—counties, towns, cities—the Web sleuths collected data that spanned state lines, allowing them to notice that a body that turned up in one jurisdiction might actually be tied to a person who had gone missing in another jurisdiction, sometimes only across a county line.”

In the cases Halber chronicled, families had been searching for years and dealing with the living hell of not knowing what had become of their loved ones. The Web sleuths, “on top of their own job and family responsibilities, volunteer countless hours, poring over gruesome images and details, mired in other people’s misery and horror, with no guarantee that they will get anywhere, or if they do, that they will receive any recognition or reward beyond the knowledge that they helped provide closure for a stranger.”

–

-“An integral component of NamUs is the group of responsible, dedicated volunteers who scour case details in an effort to match long-term missing persons to unidentified decedents. In The Skeleton Crew, Deborah Halber follows the journey of some of these volunteers who have made it their mission to assist criminal justice professionals in resolving those cases.” (Arthur Eisenberg, PhD, Co-Director, UNT Center for Human Identification)

–

“From home-computer screens to a new national database, join The Skeleton Crew for a page-turning behind-the-scenes look at the world of Internet sleuths who give names to the men and women who have died without identity. For the first time ever, readers are brought the real-life cases of missing persons, the unidentified dead, and the network of people that gives them their names . . . proving once again what I said at the conclusion of every episode of America’s Most Wanted: ‘One person can make a difference.’” (John Walsh, host of America’s Most Wanted).